Gaussian quadrature is not optimal

It’s conventional wisdom that Gaussian quadrature is the most point-efficient quadrature formula for analytic functions. But, it’s not true! “New quadrature formulas from conformal maps” by Hale and Trefethen (2008) demonstrates that it’s possible to have quadrature formulas that converge about 50% faster for analytic functions. The paper is quite accessible and I encourage you to read it, but I also wanted to help bring attention to it since it seems like it should be more well-known.

Polynomials vs analytic functions

So, where did the misconception that Gaussian quadrature is the best possible quadrature rule for smooth functions? I think it comes from framing the problem in terms of the maximum order of polynomial that can be integrated exactly. By that metric, Gaussian quadrature is the best that can be done. If we write down a quadrature rule like:

\begin{equation} \int_{-1}^{1} f(x) dx \approx \sum_{k}^n w_k f(x_k) \end{equation}

then there are $n$ points, $x_k$, and $n$ weights $w_k$. Solving a linear system for the points and weights that exactly integrate a polynomial results in a solvable linear system with $2n$ rows and columns. And a polynomial with order $2n-1$ has $2n$ coefficients, so Gaussian quadrature is clearly optimal in the order of polynomial integrable with $N$ points and weights (this isn’t a rigorous proof).

Because analytic functions can be represented as a polynomial series, it’s tempting to extend the result from polynomials to analytic functions. But, it does not follow that the best quadrature rule for small polynomials is also the best possible quadrature rule for general analytic functions or even the best possible quadrature rule for polynomials with order greater than $2n - 1$. As the Hale and Trefethen paper demonstrates, Gaussian quadrature is suboptimal by approximately a factor of $\pi/2$ in terms of the number of quadrature points required for a given level of error.

Just give me a quadrature rule

There are several formulas in the paper, but this one is particularly useful. If we have an existing Gaussian quadrature rule specified by $x_k$ and $w_k$, then we can derive a new mapped quadrature rule, $\tilde{x}_k$, $\tilde{w}_k$ with the formula: \begin{align} \tilde{I}_n(f) &= \sum_k^n \tilde{w}_k f(\tilde{x}_k) , ~~~ \tilde{w}_k = w_kg’(x_k), ~~~ \tilde{x}_k=g(x_k) \\ g(s) &= \frac{1}{53089}(40320s + 6720s^3 + 3024s^5 + 1800s^7 + 1225s^9) \end{align}

Why does this work?

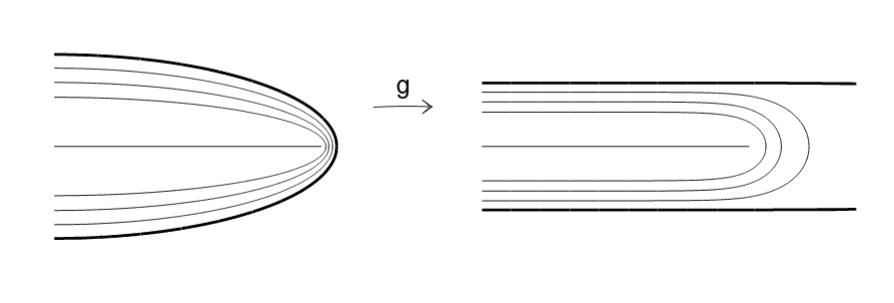

In traditional convergence proofs for Gaussian quadrature, we must assume a little bit more than just having an analytic integrand. The standard approach is to assume that $f(x)$ is analytic in an elliptical domain in the complex plane surrounding the real line segment $[-1, 1]$. The left side of the figure below is showing the right-hand half of such an ellipse. The thing to note is that this is an unbalanced regularity requirement:

- near $x=\pm 1$, $f(x)$ is allowed to have singularities or other non-analytic behavior very nearby.

- on the other hand, near $x=0$, $f(x)$ has a very wide domain in which it is analytic.

Basically, we’re putting much more stringent requirements on the center of the domain than on the end points of the domain. The idea in the Hale and Trefethen is to perform a conformal mapping of this ellipse into a domain that is more balanced. This is demonstrated graphically in the figure below.

Does this actually work?

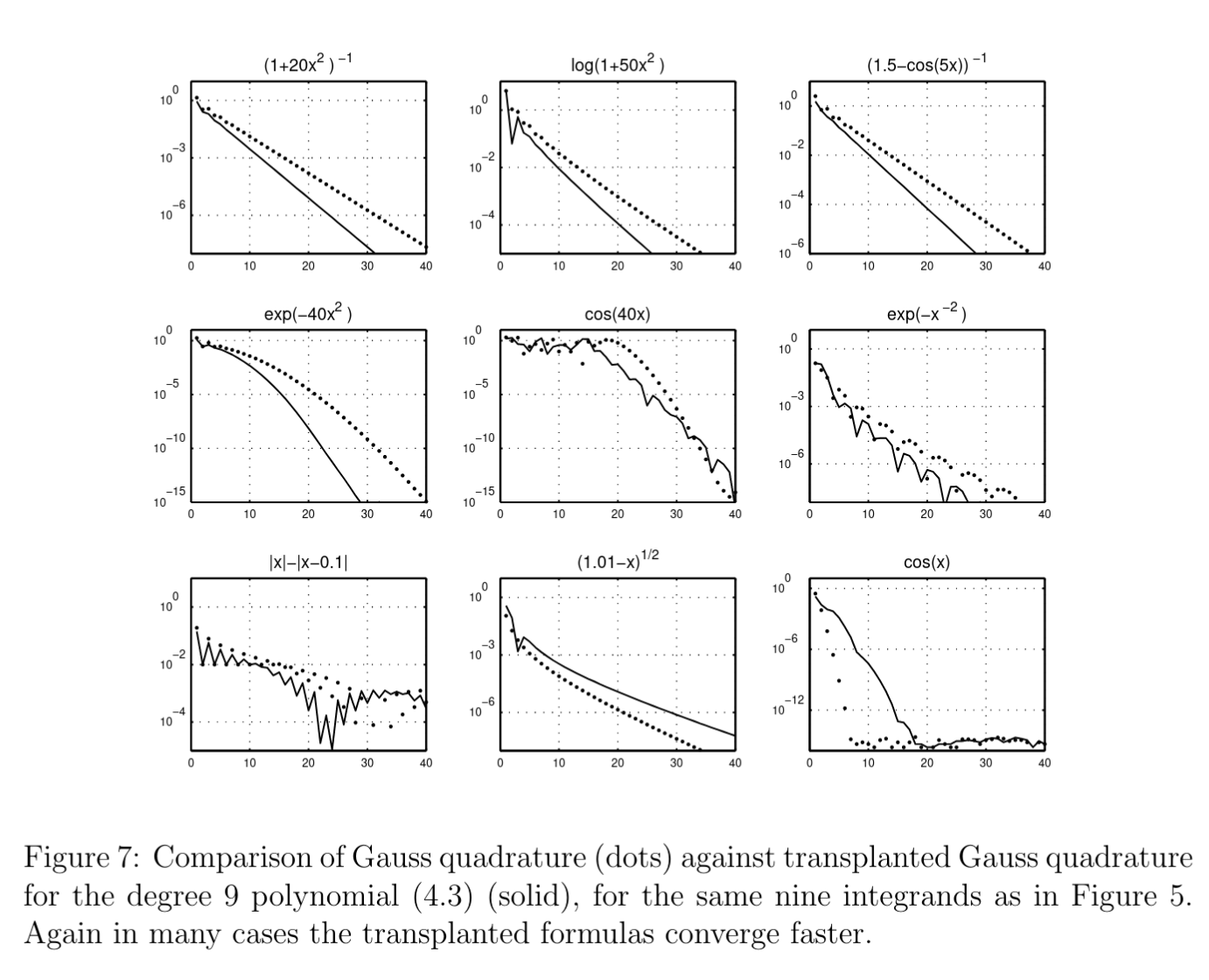

For this, I’ll just copy the figure from the paper. It depends on the integrand, but for many analytic functions, yes, the new quadrature rule is more point efficient! For further explanation of the successes and failures here, go take a look at the paper!

More myths!

Check out this Lloyd Trefethen essay for several other myths about polynomials and numerical methods.